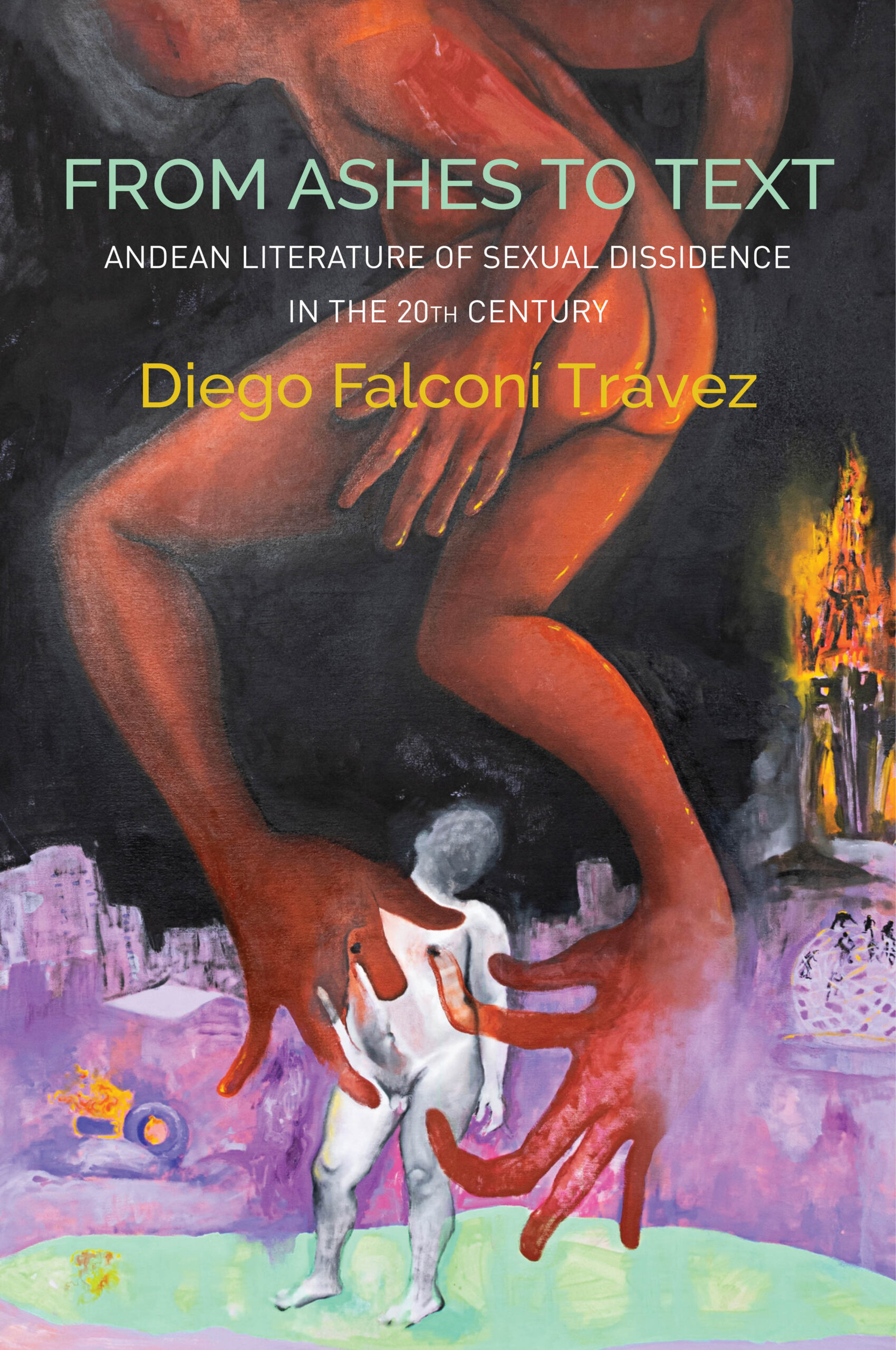

From Ashes to Text

Andean Literature of Sexual Dissidence in the 20th Century

Diego Falconí Trávez / Translated by Carrie Hamilton

November 2022

According to some chronicles of the Spanish Conquest, the violent arrival of the Conquerors to the Andes in the sixteenth century led to sex-dissident people who lived outside the dominant European cisheteropatriarchal model being burned at the stake. This act burned more than the flesh; it also charred practices, ways of life, and textualities, leaving an emptiness and a trauma that would mark the future literatures of the Andean region.

This book cannot repair those pre-sodomite texts and bodies. It seeks instead to reconsider the value of the ash, a metaphor that allows for a critical and contradictory reading of sexual dissidences in the Andean region in the twentieth century, beyond both multiculturalism and the wake of a globalized LGBTI movement. Through a comparative analysis, and drawing on theoretical perspectives such as anticoloniality, feminisms, and cuir (rather than queer) theories, the book aims to understand the value of a series of complex texts in which dissident subjectivities, practices, and desires help to broaden the understanding of the Andean.

Winner of the prestigious Casa de las Américas prize, the book was praised by the jury for the paradoxical and provocative way that it struggles against the abyss of past destruction and reflects on the contribution of the Global South to the often uniformist thinking around the body and its intersections.

That fantasy, which is found in the chronicles, resulted in a genocide[1] – or, according to the strictest historiography, a protogenocide – which operated from a sex-gender and racial perspective, and installed itself in Andean time and space.

Although the Andean sodomite quasi-characters therefore practiced the same vice as, for example, the sodomites of Valencia (Catalá Sanz and Pérez García, 2000: 31), they would never be the equals of their European counterparts. This was not just because they were “closer to the end” of the chain of command (the non-sovereign, the invert), but because their cultural alterity – ethnic, sexual, and political – was a sentence not only for the disappearance of the act of sodomy or the life tainted as sodomite; there was also the potential to condemn their entire population to extermination. By this virtue, the sodomite/abominable actant in the Andean zone is an intertextual straw doll covered with the power of the written word (Dussel, 1992), stripped of the signifiers of full humanity and of the diverse potential of the pre-Hispanic sex-dissident subject.

Thanks to the fire metaphor,[2] and to the ideological embers made flesh, the body and the sin were carbonized in the text; subjectivity and the entire population were condemned. And since written memory erased both native vitality and resistance, there had to be a guarantee that the smoke from certain recurring practices (which seemed endemic to certain populations)11[3] would placate the annexed and conquered territories.

The antisodomy flame was not quenched following the tales of extreme disciplining recounted in the chronicles. It continued to burn with the desire for eternal vigilance in sentences and other texts, prescribing punishments so that new bodies that were declared sinful in the conquered territories (mestizo, Afro-Andean, and Indigenous bodies) would disappear, once again, from the face of the earth. In fact, not only was the legal-religious letter entrusted with the fate of the sodomite; written and visual texts were brought together with the aim of amplifying the record of condemnation. In Hernando de la Cruz’s painting El infierno o las llamas infernales (Hell or the Infernal Flames, 1620),[4] a kind of seventeenth-century graphic penal code, the crime NEFANDO (ABOMINABLE) appears written in golden letters, alongside a drawing of the punishment of the accused (a double rip in the chest at the level of the heart and an attack by demons, interpreted as eternal sexual harassment and assault, before the attentive gaze of one of the heads of Cerberus). The text not only testifies to the torture of the sex-dissident Andean body, but also to the complex construction of archives in a society with new embodiments and new cultures, in which writing had to mutate toward other forms of recording.

Andean sodomy was, ironically, the only referent for the knowledge that certain bodily practices had existed, practices that were different from those imposed by colonization. This paradox – having to incarnate the typology that was exterminated in practice – has led us to collect fragments of identity that could not be completely assembled during the colonial, independence, and republican periods, or even in the era of regional construction, during which the sodomites (Indigenous, Afro-descendant, mestizo, and white) had no safe space in which to travel, either inside or outside the text.

Not even those written proposals that researched into ancestral cultures in the most dignifying way, such as Indigenism (for example, in the debates between Luis Valcárcel and Uriel García on how to guarantee native continuity from a mestizo perspective – see Funes, 2006: 146–53),[5] were able to propose this pre-abominable re-composition, which is extinct in their radical demands and writings – a fact that demonstrates the force that certain destructive discourses had on certain bodies. Nor did those subjectivities that had been concealed by sodomy appear in the revisionist writings of the twentieth century,[6] with their globalized LGBTI identities. These texts did not look backwards in order to call, through the expression of their pride, upon an entity whose stories are so far removed from their own demands.

After all, would anyone miss a being who was more fantastical than real and who, if they were to reappear, could once again lay bare the most brutal face of the Conquest – for being diametrically opposed to the sovereign, for being the face that opposed the conqueror’s cross? Was it worth thinking about the character of the sodomite, one grotesquely filled with the distorted signifiers of native peoples who spoke of non-power? Would it be of any use to consider those bodies of the past, uncertain and erased from collective memory in the era of the re-composition of a globalized LGBTI movement?

In the face of such questions, perhaps reflection is in order: the carbonized body has not disappeared altogether; its ashes remain as a powerful trope of absence. In the chronicles, in fact, this stain that is left by the remains of the abominable has been discreet but indelible for the region’s subsequent bodily and textual itinerary. In the case of the sodomite, the ash does not constitute a vital narrative opening, the seed that García Márquez spoke of, but rather the spoils of history, the trope of the solitude, affliction, and loss that remain after any annihilation. By symbolizing Andean sodomite trauma, the sodomite ash is a key element for understanding the colonial paranoias that are still repeated on the narrative templates of corporeal hierarchization, simplistic characterization, and extreme violence. But it also offers a key to the possibility of working on the past in order to refocus ways of considering texts and their possible incarnations.

In this book, which focuses on the literature of the complex twentieth century, I hold on to these chronicles – distant, imprecise, and troubling as they are – because they are located in a place where history makes its way through fiction (O’Gorman, 2002: 61), giving them a testimonial[7] and creative value in which the person and the character come together; in which a particular mode of historicization is activated – one that ironically calls for the desacralization of history in order to allow for the reconstruction of memory; in which a certain ethical commotion forces us to acknowledge the pain of others (Sontag, 2003), which is also our own pain, although a fictional and fantastical lifeline protects us from succumbing to the horror.

From this, a product of catharsis, but also of debt – something fundamental to the (re)construction of any community (Baas, 2008: 11) – it is possible today to ask ourselves, in a less naive way: which structures of the colonial sodomite tale still remained in the twentieth century? Were any legacies of these abominable presences/ absences from the chronicles to be found in more contemporary writings? Could the legal typology of the sodomite be replaced by more in-depth characterizations, so that those who came afterwards could again be characterized as subjects? Or were they also considered absurd characters in the region? What writerly tactics and strategies were used in the complex cultural field to overcome the colonial trauma that burned certain bodies and desires in the Andes? Did ancestral, Afro-Andean, and mestizo subjectivities attempt to revive those subjectivities that had been named as abominable? Could more recent writing, in a somewhat less virulent period, link together past lives and deaths in order to articulate a literary record of their own, as much Andean as it is sex-dissident?

To begin this book, which aims to put forward some answers to these questions, I situate myself in the relationship between writing and the abominable ash, final remnant of a faraway body, uncertain and buried by colonial discourses and practices. Through literary theory, comparative literature, and cultural studies, I seek to reevaluate certain transgressive subjectivities and practices in twentieth-century writings in the Andean zone that are linked to that powerful ancestral presence.

Excerpt from “Instructions for Reading this Book: By Way of an Introduction” in From Ashes to Text, 4-9, Polity Press, 2022, Translated by Carrie Hamilton.

Works Cited

Baas, Bernard (2008) El cuerpo del delito. La comunidad en deuda. Buenos Aires: Ediciones Signo.

Beceiro García, Juan Luis (1994) La mentira histórica desvelada. ¿Genocidio en América? Madrid: Ejearte.

Boswell, John (1981) Christianity, Social Tolerance, and Homosexuality. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Catalá Sanz, Jorge, and Pablo Pérez García (2000) “La pena capital en la Valencia del Quinientos.” In Conflictos y represiones en el Antiguo Régimen. Valencia: Valencia University Press, pp. 21–112.

Clavero, Bartolomé (1992) Genocidio y justicia: la Destrucción de las Indias, ayer y hoy. Madrid: Marcial Pons.

D’Emilio, John (2002) “Then and Now: The Shifting Context of Gay Historical Writing.” In The World Turned. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, pp. 210–230.

Dussel, E. (1992) El encubrimiento del otro. Hacia el origen del mito de la modernidad. Madrid: Nueva Utopía.

Falconí Trávez, Diego (2014b) “La leyenda negra marica.” In Diego Falconí Trávez et al. (eds.), Resentir lo queer en América Latina. Diálogos con/desde el Sur. Barcelona: Egales, pp. 81–116.

Federici, Silvia (2004) Caliban and the Witch: Women, the Body, and Primitive Accumulation. Brooklyn, NY: Autonomedia.

Funes, Patricia (2006) Salvar la nación: intelectuales, cultura y política en los años veinte. Buenos Aires: Prometeo Libros.

Horswell, Michael J. (2005) Decolonizing the Sodomite: Queer Tropes of Sexuality in Colonial Andean Culture. Austin: University of Texas Press.

Jara, René (1986) “Prólogo.” In René Jara and Hernán Vidal (eds.), Testimonio y literature. Minneapolis, MN: Institute for the Study of Ideologies and Literatures, pp. 333–341.

O’Gorman, Edmundo (2002) La invención de América. Mexico City: FCE.

Payne, Stanley (2017) En defensa de España: desmontando mitos y leyendas negras. Madrid: Espasa.

Pereña, Luciano (1992) Genocidio en América. Madrid: Mapfre.

Quijano, Aníbal (2000) “Colonialidad del poder, eurocentrismo y América Latina.” In Edgardo Lander (ed.), La colonialidad del saber: eurocentrismo y ciencias sociales. Perspectivas latinoamericanas. Buenos Aires: CICCUS/CLACSO, pp. 201–246.

Ramos, Demetrio (1986) “¿Genocidio a la española?” In Luciano Pereña (ed.), Doctrina Christiana y Catecismo para instrucción de los Indios. Madrid: CSIC, pp. 21–54.

Sontag, Susan (2003) Regarding the Pain of Others. London: Hamish Hamilton.

[1] Some Spanish authors have been in favor of the use of the term “genocide” from the position of a historical-legal analysis (Clavero, 1992) or based on the examination of historical documents (Pereña, 1992), even while recognizing that the word is possibly ahistorical. Other Spanish authors have criticized the term as opportunistic or ideological, claiming that it discredits Spain (Beceiro, 1994) or that extermination did not form part of the Mediterranean way of thinking (Ramos, 1986). Outside Spain, but with prestige within the Iberian Peninsula, the US historian Stanley Payne stresses that the use of “genocide” arises from twentieth-century political correctness (2017: 16). I opt to use the term “proto-genocide.” The authors who refute it do not engage in a critical revision of the tools that might enable a re-reading of history. Nor do they employ a human rights perspective, which differentiates between existence and recognition. The persistence of the debate around the “Black Legend” between Europe and the United States, which does not take into account readings that talk about racism (Quijano, 2000: 207) or heteropatriarchy (Federici, 2004: 220), reflects an impoverished and incomplete argument, lacking intersectional approaches, in which sexual orientation/desire, race, class, etc. are central. I develop this critique in my article “La leyenda negra marica: una crítica comparatista desde el Sur a la teoría queer hispana” (Falconí Trávez, 2014b).

[2] I use the fire metaphor because, as Horswell notes, it is dangerous to go to the “original meaning” of the tales (2005: 95).

[3] I refer to the populations of the zones with warm climates, who were seen in the colonial imaginary as having a greater propensity to commit the abominable sin.

[4] The painting is located in the Church of the Society of Jesus, the first Jesuit temple in Quito. The original dates from 1620 and in 1879, in a state of deterioration, it was replaced by a replica.

[5] Translator’s note: Luis Valcárcel and Uriel García were Peruvian intellectuals and part of the Indigenist movement of the 1920s.

[6] Take, for example, John Boswell’s famous historical work, Christianity, Social Tolerance, and Homosexuality, published in 1981. Boswell analyzes the existence of gay subjectivities (with the problematic nature of that term) in Western Europe from antiquity to the Middle Ages. The only references to other, non-Western forms of sodomy occur when the author vaguely mentions that “even among primitive peoples some connection is often assumed between spirituality or mysticism and homosexuality” (1981: 27) and in a footnote where he refers to berdache subjectivities, among others. The gay historian John D’Emilio, who focuses on gay narratives in the United States, defines the routes toward a gay historiography in very vague terms: “Only in some societies and eras do desires coalesce into a social role, or identity, that gets labeled homosexual, or gay, or lesbian, and that corresponds to how individuals organize their emotional, intimate, and erotic lives. And, for reasons that still can only remain speculative, the modern West appears to be one such place and time” (2002: 221–2).

[7] I am not trying to make a de-problematized link between twentieth-century testimonio – which has been so developed and studied in Latin America – and the colonial chronicles. Nevertheless, I do share the vision of some authors who have studied the genre of testimonio and claim that this is a historical genre in the region (Jara, 1986), one that has appeared over and over, although in complex and contradictory ways.

Interview with Diego Falconí, La Periódica, June 2017.

Performance, "De las cenizas al texto," 2017.

About the Author